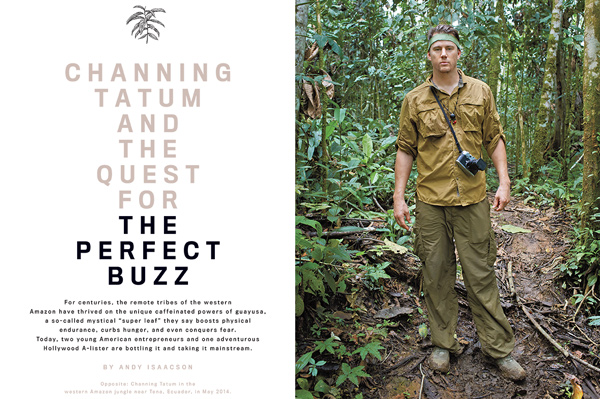

FIRST PUBLISHED IN MEN'S FITNESS, MARCH 2015

CHANNING TATUM HAS A RECURRING DREAM in which he sprints furiously across an unfamiliar landscape, then, arms outstretched, takes flight, soaring above the terrain like a hang glider. A version of this dream comes to him one night in spring of 2014, while dozing in a hammock deep inside Ecuador’s rainforest. This time he runs up a hill dotted with tall trees. At the crest stands a forbidding wall that rises as he draws nearer. Barefoot, he bounds up the wall and, reaching the top, sees a vast territory unfurling toward the horizon. He pauses, then plunges down the other side.

The next morning Tatum recounts the details of the dream to a group of us sitting on tree stumps around a smoldering fire, in a remote indigenous Sápara settlement near the border of Peru. The villagers have painted our cheeks with a reddish pigment made from tree seeds, issued us each Sápara names (Tatum takes “Tsamaraw,” which means “protector spirit”), and blown tobacco smoke into our faces to expel negative energy.

In our hands are coconut shells that contain a caffeinated elixir we’ve traveled 4,000 miles to find: guayusa, a plant native to the western Amazon, whose green, elliptical leaves have been a staple of the region’s indigenous populations for thousands of years.

The Sápara drink guayusa (“gwhy-YOU-sa”) for stamina, and as a tool to interpret dreams. Shipibo medicine men in Peru prescribe a strong, guayusa-based drink to patients who suffer from trauma, as a way to conquer fear. The Kichwa people, in Ecuador’s northern jungle, say the plant also kills hunger, and often pack guayusa leaves as their only sustenance on long hunting expeditions.

A Kichwa man had described to me the mystical circumstances surrounding the discovery of the plant’s energy-boosting properties. It was during an era of tribal warfare; one night the spirit of a tree told a sleeping Kichwa sentinel, “Hey friend, I can help you.” The sentinel awoke to find a bush rustling nearby. He chewed its leaves, and immediately felt alert and animated. Today the Kichwa refer to guayusa as “the night watchman’s plant.”

Tatum, the star of Foxcatcher and this summer’s Magic Mike XXL, has come to the Amazon to sample the plant for a different reason. An investor in the New York-based beverage startup Runa (a Kichwa word meaning “fully alive”), the first company to produce drinks containing guayusa, he wants to learn everything there is to know about it. We’ve spent the last few days with Runa’s co-founders, Tyler Gage and Dan MacCombie, drinking, farming, and literally bathing in guayusa as women pour bucketfuls over our heads.

Gage and MacCombie represent the latest entrepreneurial rush into the rainforest—a place from which, in recent years, marketers have emerged with billion-dollar beverage products like açai. Leveraging Tatum’s celebrity, the pair hope to break into the $30 billion energy drink market, a field dominated by Red Bull and brands like Monster Beverage, which has concocted a juggernaut out of guarana, another caffeinated Amazonian plant. Trouble is, unlike guarana, few people have heard of guayusa. Tatum, Runa’s unofficial spokesman (his exact role is still being hashed out), hopes to change that.

After Tatum finishes describing his dream, a soft-spoken Sápara man focuses on him: “Your running represents the instinct of always striving to go further,” he says. “By making it to the top, you made it in your personal, professional, and spiritual life—there is nowhere else to go. But that expanse on the other side: That is the platform to recognize who you truly are.”

I wait for Tatum to lighten the mood. After all, this is the Jump Street star whose dick jokes have gone viral. He’s also a well-known prankster off camera. In fact, earlier this trip, he yanked me from a raft into a fast-flowing river and goaded me into eating a squirming grub from a palm tree. I expect him to respond to this shamanic psychoanalysis with a self-deprecating joke.

Instead Tatum nods along earnestly, pauses, then takes a sip from his coconut shell and launches into yet another dream, about waking up in a room from which he can’t escape. “This happens a lot,” he begins, “and I wonder what it means...”

The day before, at Runa’s factory in Archidona, Ecuador, Gage, MacCombie, Tatum, and his producing partner, Reid Carolin, take a tour of the company’s guayusa factory. Inside a low-slung white building covered in plastic, a woman in hospital scrubs and a surgical mask stirs beds of leaves, allowing them to dry and oxidize. They smell pleasant, like freshly cut grass, and Tatum snatches a pile and burrows his nose in it. He and Carolin first discovered Runa at a Whole Foods in New Orleans while shooting 21 Jump Street, in 2011, and the drink became their lifeblood as they raced to finish the Magic Mike script. “We were hammering it like it was a drug,” says Tatum. “Runa went in smooth and left smooth, and gave a longer buzz than coffee.” He now starts every day with a can of it. The next morning, I watch as he slams one then backflips off a 50-foot bridge into a river.

An 8.4-oz can of Runa’s energy drink comes in two flavors: Berry, with 17 grams of sugar, and Original Zero, a sugar-free version. Both have 120 milligrams of caffeine from guayusa leaves, which are dried in Archidona, shipped to a facility in New Jersey, then brewed into the carbonated energy drinks as well as a line of glass-bottled teas flavored with mint, hibiscus, and lemongrass.

Before Gage and MacCombie launched their company, not a single scientific paper had been written about guayusa. The Kichwa people say the plant can replace food on lengthy jungle trips. Both Gage and Tatum say that after drinking guayusa, they feel a pleasant boost without the jitters coffee gives them. “I needed something that gave me a longer burn and didn’t leave me cracked out,” says Tatum. Gage recalls a curious sensation the first time he drank guayusa. “I felt very awake but rooted at the same time,” he says. “I wasn’t sure why, but it was striking to me.”

Recent research conducted by Applied Food Sciences, a U.S. supplement firm that plans to market guayusa extract, offers evidence to support the “slow burn” claim. The plant is part of the holly family, and appears to offer the virtues of both tea and coffee: Its leaves contain significant levels of various antioxidants, including the catechins found in green tea, which reputedly fight cancer and boost metabolism, and the chlorogenic acid in unroasted coffee beans, which spurs weight loss by slowing the uptake of glucose from the intestines.

In addition to natural caffeine, guayusa also contains theobromine, a stimulant abundant in chocolate. Ounce for ounce, there’s less caffeine in guayusa than in dark roast coffee, but for reasons not yet well understood—having to do with the synergistic effects of these various compounds—the body metabolizes the caffeine in guayusa over a longer period of time.

“For endurance athletes who’d like to have more of a sustained release if they’re doing something more than a quick run—this really helps for that,” says Chris Fields, vice president of scientific affairs at Applied Food Sciences, which is starting clinical trials to investigate guayusa. “It’s a really unique plant, and now we seem to understand why it’s been used for centuries by Amazonian groups—it has so many medicinal benefits.”

Guayusa lacks tannins, the compounds in green and black tea that give it its bitter, puckery quality. When I drink a 14-oz bottle of Guavo Zero Unsweetened Runa, it tastes like watered-down tea. The first thing I notice sipping an 8.4-oz can of Runa Original Zero (with a hint of lime) is a sharp acidic tinge of artificial lime that instantly dissolves into a leafy, tea-ish aftertaste. The fizzy, one- two punch reminds me more of a store-bought Arnold Palmer than it does a syrupy Red Bull. (This is not a bad thing.)

Guayusa’s energy kick is gradual, more tortoise than hare. After one serving, I feel a subtle caffeine lift, rather than a spike. (For those who rely on the jolt of a Grande Pike Place or Monster, take note.) Two servings later, though, my body feels alert, and I’m humming along like a machine. I can see why Tatum and Carolin drink it during script-writing marathons. “The whole reason we [embraced Runa],” says Carolin, “was because we saw the effect this product had on our creativity.”

By offering a product with this unique rush, and by touting its claim of clean energy, Runa hopes to muscle into a marketplace cluttered with less healthy choices. The definition of “energy drinks” is somewhat elastic—they’re marketed as dietary supplements—but all tend to share large doses of caffeine combined with taurine, glucuronolactone, carnitine, B vitamins, and ginseng, various forms of stimulants, which, in excess, can give rise to harmful side effects. Most energy drinks also pack lots of sugar. An 8.4-oz can of non- diet Red Bull has nearly seven teaspoons of added sugar. (The American Heart Association advises no more than nine teaspoons of added sugar a day for men.)

Though the health effects of all the various chemical and herbal ingredients used in energy drinks and their possible interactions with caffeine are largely untested, the consequences of excess caffeine consumption are well understood: tachycardia, arrhythmia, hypertension, seizures, insomnia, and anxiety. According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a health advocacy group, FDA documents show that in the past decade, 34 deaths have been linked to, and possibly caused by, energy drinks. “Energy drinks are clearly causing symptomatic arrhythmias,” says Stacy Fisher, M.D., director of complex heart diseases at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Market research firm Mintel reported last year that nearly six in 10 Americans who consume energy drinks or shots—mostly 18– to 24-year-olds—say they now worry about their health.

“Right now, our low-hanging fruit is reluctant Red Bull drinkers who are like, ‘I drink this stuff but I know I shouldn’t, I know there’s something better’—which I think is a huge audience,” Gage says. “We just need to communicate in the right way to get them.”

Guayusa had never been grown commercially until five years ago, when Gage and MacCombie, two friends from Brown University, began shipping bags of the leaves to the U.S. Today Runa is sold in 7,000 stores across the country, including Safeway, Whole Foods, and Vitamin Shoppe. Last year, the company took in $2 million in sales; this year it’s on track to make $8 million. Runa has also attracted an eclectic mix of investors, including responsAbility, a Swiss sustainable management fund; a successful musician and producer named Dr. Luke; and the founder of Zico coconut water, Mark Rampolla.

Another investor, New York artist Neil Grayson, who’s a friend of Tatum’s and knew of the actor’s taste for Runa, connected him with Gage in 2013. Tatum immediately noted an auspicious coincidence: The character he’d played in his 2006 breakout film Step Up was also named Tyler Gage. If for no other reason, he tells me, “the sheer sake of weirdness” piqued his business interest in Runa.

Gage first tasted guayusa in 2005, after his freshman year in college, when he was in Costa Rica doing research with an American ethnobotanist. At the time, Gage, who’d been recruited to play soccer at Brown, was obsessed with health, nutrition, and peak performance. He’d tried going vegan for 18 months and Paleo for a spell, and even experimented with lucid dreaming. “I was interested in what the human mind has the capacity to do,” he says.

Eventually Gage came upon books by a decorated triathlete named Mark Allen, who’d studied the teachings of a Huichol shaman from Mexico. “He was relatable to me, from an athletic performance point of view,” says Gage, who reached out to Allen after his freshman year. “This wasn’t a dude who believes in spirits and wooah. No—homie won the freaking Ironman six times, and he attributes his success to the strength he learned with shamanism.”

Gage studied with Allen, who inspired him to study plant medicine in the Peruvian Amazon. There, for college credit, Gage researched the ethnolinguistics of the Shipibo people, while the Shipibo shamans put him through intensive ceremonies and diets. “Every day I had to get up at sunrise, drink these gnarly plants, and basically sit out in the jungle by myself,” he says. “It was really intense and really cool. And I can’t really explain it, but that’s when I remember feeling things shifted inside me.”

When Gage got back to Brown, his friend MacCombie was enrolling in a class on social entrepreneurship; he dragged Gage along. The course required that they write a business plan. In Peru, Gage had seen how Amazonian communities are often drawn into business with oil and logging companies for lack of any economic alternatives, so the two conceived of a company selling a guayusa-based beverage. As far as they were concerned, it was a class exercise. But their professor—an entrepreneur named Danny Warshay, who’d worked for Duncan Hines—urged them to think otherwise. “It hadn’t even crossed our minds,” Gage confesses. Over late nights, however, the idea marinated. In December 2008, two days after he and MacCombie graduated, they flew to Ecuador.

After six months of backpacking among villages to secure guayusa suppliers, Gage and MacCombie landed a $50,000 small business grant from Ecuador’s Ministry of Export, which in 2010 they used to build Runa’s first research facility, a steel drying-chamber in a bamboo garage full of chickens. Larger grants from the Ecuadorean government and the U.S. Agency for International Development allowed them to build the first real Runa factory. They shipped guayusa back to the States and managed to sell the first boxes to Whole Foods. At a natural foods trade show in 2011, Gage and MacCombie were hawking samples of their “Amazonian tea” from a remote corner booth when Neil Kimberley, former brand director at Snapple, happened by and offered to help formulate their product. “You guys seem pretty cool,” he told them. “Give me a call.” He’s now on Runa’s board of advisors.

Today, Runa’s harvest comes from over 3,000 local farmers, who tend the bushy plant in traditional gardens called chakras. The company’s also launched a nonprofit that funds the largest reforestation program in the Ecuadorian Amazon, partly supported by the MacArthur Foundation, and is also helping guayusa farmers form cooperatives.

We’re sitting on a grassy airstrip beside another Sápara settlement when Gage reaches into a cardboard box and pulls out a few prototypes of the Runa energy drink can, which prominently features a guayusa leaf and the words “Clean Energy.” One of Runa’s investors, Kim Jeffery, who, as the president and CEO of Nestlé Waters North America, had helped turn it into the continent’s third-largest beverage company, has advised Gage on the importance of a clear, succinct message. “His thing is: You have three seconds to tell people what your product is,” Gage says. “What we want people to say about Runa is not that it’s tea, or light tea, but that it’s better than tea. Categorically better, and categorically different.”

Tatum doubts whether the can’s current design accomplishes that. “One thing Red Bull has done really well is that it can be sitting all the way over there, even in the dark, and you know exactly what it is,” he says, pointing across the runway. “Just, bang—I know it. So, the leaf: I know that’s what it is. But is that what we’re advertising? What are we trying to get people to understand? The biggest thing for me is to figure out how to key into exactly what it should be used for and what it’s going to deliver. It’s alive. It sharpens you. It gives you insight into your world—focused presence, not just jacked up. The packaging should say what it’s going to do for you. Then if people wonder what it’s made from, they’ll turn it over and read the ingredients and find out it’s natural and it’s made from a leaf in South America.”

Carolin adds, “I think people want to feel like they’re holding a symbol in their hand, and that’s what Red Bull has become.”

“You’ve got to make it cool to drink,” says Tatum. “I hate to be some kind of idiot American saying that, but look—you can’t deny the product. It makes you run faster, jump higher. Now you just have to—.”

“Put the ‘swoosh’ on it,” Carolin says. “Yes!” insists Tatum. “That thing that says: This is why it’s fucking cool.” Gage, for his part, wants people to think of Runa as an alternative to Red Bull in a way that some now see Vita Coca—the country’s top-selling coconut water brand—as a replacement for Gatorade. His challenge is to distinguish guayusa from tea, and somehow make it hip. “This is 99% of what’s going to determine if we’re a $10 million company or a $500 million company,” says Gage.

Yet he recognizes this is all nearly impossible without someone like Channing Tatum. In 2011, Vita Coco, whose celebrity investors include Madonna and Rihanna, ran a billboard campaign that featured Rihanna urging consumers to “Hydrate naturally from a tree, not a lab”—a jab at Gatorade and Powerade. That year the company saw its revenue double to nearly $100 million.

To date, Runa’s celebrity weaponry has been small gauge. The company sends products to a “Runa Tribe” made up of athletes like wakeboard world champion Darin Shapiro and pro kiteboarder Damien LeRoy—“individuals who embody what it means to be Runa,” according to the company’s website—hoping they’ll spread the gospel. But the star power of Tatum, Runa’s unofficial pitchman—he’s discussing with the company various ways they might leverage his celebrity—actually has the potential to blast the brand into the mainstream. “We’re dealing with guys [Tatum and Carolin] whose entire professional business is public entertainment, and what’s cool and sexy. And they’ve been successful at that. Channing has his finger on the pulse of the average American: what they do, how they think, and what they want.”

A few weeks after returning from the Amazon, Tatum, in preparation for Magic Mike XXL, begins a 10-week regimen with celebrity trainer Arin Babaian to mold his body back into male stripper form—workouts fueled by guayusa. “We buy into things we believe in, and this is something I can completely get behind,” he says on our way back from Ecuador. “Someone can just be like, ‘Oh, you’re just getting paid for this, right?’ and I can say, ‘No, I actually just drink the shit out of it.’” ■